Have you noticed things seem to be getting a little worse in the developed world? Australia voting a resounding No on the weakest, most milquetoast concession to acknowledging and amending its colonial crimes, the Middle East’s Only Democracy(TM) going on a wild killing spree, unprecedented global heat at the same time as governments of the world’s richest nations are canceling basic infrastructure plans, reneging on carbon reduction commitments, and getting into weird culture war battles about how to define a woman? Things seeming a little desperate? It appears we have reached the stage just after the “and” in the famous phrase “scratch a liberal and a fascist bleeds”.

Canada’s Liberals Applaud a Nazi

The mask really slipped a few weeks ago when Ukraine’s president Zelensky visited Canada to beg for weapons. The war in Ukraine isn’t going well, and the much-vaunted wunderwaffen donated by the west – German tanks rolling into Eastern Europe for the first time in 80 years – have failed to advance the promised counter-offensive, though Ukraine’s leadership has made sure that the offensive achieves the US’s goal of fighting Russia to the last Ukrainian. With video of NATO’s supposedly superior “kit” (ugh) getting wasted on the battlefield proliferating, no progress in the war, and the US house getting skittish about signing more blank checks, Zelensky needed to shore up his support among his allies. After Zelensky’s speech to the Canadian parliament, an apparently well-meaning Canadian speaker introduced a 98 year old man who he told everyone “had fought for Ukrainian independence against the Soviet Union in world war 2”, with Liberal PM Trudeau leading Zelensky and the parliament in two rounds of standing ovations for this stalwart of freedom.

Apparently nobody bothered to think what kind of man might have “fought against the Soviet Union” for Ukraine in world war 2, and of course it turned out very quickly that the man in question was a member of the Waffen SS. Canada’s parliament somehow tricked a Jewish head of state (Zelensky is Jewish) into giving a standing ovation for an Actual Nazi, just because he fought the Soviet Union.

This is a kind of treason, of course: the Soviet Union were Canada’s allies in world war 2, fighting the Nazis, and suffered horrifying losses during their retreat from and recapture of Ukraine. Applauding someone who fought them makes a mockery of their sacrifice, shows the ignorance of all assembled towards their own history, conflates modern Russia with the Soviet Union (a common mistake among liberal apologists for our ridiculous support of Ukraine), and – most importantly – means applauding a nazi.

The 14th Waffen SS division of which Hunka was a member wasn’t an innocent bystander in the war either. They did partisan suppression duties in Poland and Ukraine, freeing up regular SS and Wehrmacht units to kill Soviet soldiers, and in some instances destroyed whole villages. They probably helped with round-ups of Jews, and of course by providing support services they freed up regular units of the SS in Ukraine to speed up their activities in the Holocaust. Himmler himself visited the unit, and said some pretty horrifying things indicating he knew full well where their racial solidarity lay. The knowledge of this unit’s activities isn’t dead in Ukraine, either, far from it – you might recognize their symbol on the Wikipedia page as a common symbol on Ukrainian soldiers uniforms, and in the year before the war started the unit was celebrated in Kyiv. It’s likely that in that horrific display of Nazi solidarity in the Canadian parliament Zelensky, at least, knew about the unit’s history, since it’s a matter of public celebration in certain sectors of Ukraine’s political class, including the people who surround Zelensky.

When Nazis aren’t Nazis

There’s a joke going around the internet that since the Ukraine war began western media have slid through stages of Nazi-denialism, from “there are no Nazis in Ukraine” to “Oh, there’s just a few” to “they aren’t so bad” to, finally “Being a Nazi isn’t always wrong anyway”. It appears we’ve reached stage 4, because within a few days Politico EU published an article arguing that being in the SS didn’t make you a Nazi. Now there’s a reversal on the Nuremberg Trials, eh! Then there was a lot of talk about well how could they have known that these guys fighting in Ukraine against the Soviet Union were Nazis, and he probably wasn’t a volunteer anyway (he was). Then it began to become clear that the Canadian government had courted these Nazis after the war, and a whole bunch of horror stories began to emerge about monuments to the Nazis in Edmonton, an endowment in this Nazi’s name to a Canadian university, and, well, a generally sordid past of encouraging these treacherous villains to contribute to culture and history in Ukraine.

It should be noted that Canadian scholarship on Ukraine was an important contributor to the development of the contested theory of the Holodomor, the idea that Stalin deliberately starved Ukraine. This idea was not new in Ukraine, but the word itself appears to date from the 1980s or 1990s, and it’s likely a fabrication of these Canadian Ukrainian scholars, many of whom were former Nazis. One person who has contributed to the popularization of this claim is Anne Applebaum, who is a regular contributor to liberal publications like the Atlantic and has been a vociferous proponent of the idea that Russia is committing genocide in Ukraine. Her book Red Famine, which contributed to the popularization of this genocide myth, is no doubt heavily influenced by these Canadian-Ukrainian scholars, but she has been perfectly silent about the revelation that they were all Nazis. This body of recent work on the Holodomor feeds into a wider anti-semitic current, known as “double-genocide theory“, which holds that Stalin was as bad as Hitler and is often implicitly or explicitly cited as a justification for Ukrainian (and other countries’) support for the Nazis. This dangerous elevation of a high-school debate bro fetish to the level of serious legal and scholarly work is dangerous, particularly for anti-fascists in Eastern Europe, but it’s a surprise to see it bubbling to the surface in such a grotesque way in Canada.

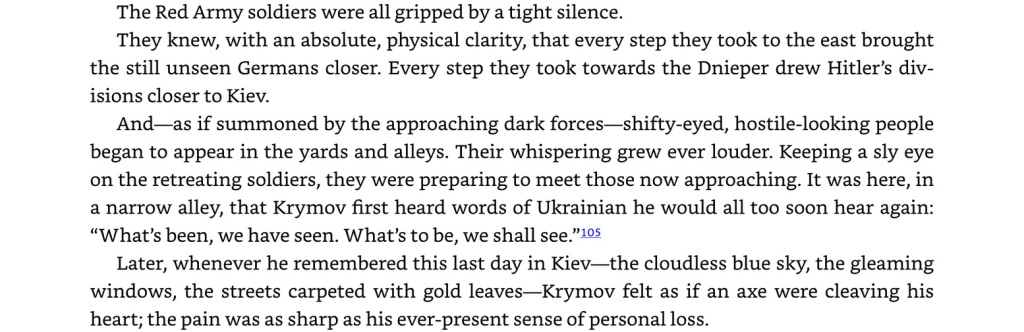

Russians, of course, have no illusions about this double-genocide nonsense, the evils of Nazis or the nature and persistence of Ukrainian Nazism. Here is what Vassily Grossman had to say about the looming threat of Nazi collaboration in Ukraine in his famous book Stalingrad:

This is the background to the growth of Red Sector, the Azov battalion and the neo-Nazis who humiliated Zelensky in 2019 and forced Ukraine down the road to the war. This is the reason that to get to Baby Yar – the site of the infamous 1941 massacre – and the memorial erected there by the Soviet government, traveling from the Eastern side of Kyiv your quickest route will be along Stepan Bandera avenue. But all this history has been wiped from liberal memory in the west, in the post-war scramble to redefine the Soviet Union as the Enemy, and to rewrite the history of the war so that the allies’ relatively small contribution – and much smaller sacrifice – could be raised above the great and catastrophic suffering of the Soviet Union, obscure the allies’ failure to rescue the Jews, and airbrush the Soviet Union’s central role in saving Jews from the Holocaust out of our history. And how is that working out, now?

The West’s guilty conscience lashes out

Some simple facts about the West’s culpability for the Holocaust should be well known but are relatively underplayed in Western history lessons. From 1939 when the Nazis started the war to the middle of 1944 there is almost no evidence of significant resistance against the Nazis west of the Danube. In Poland and Ukraine yes, there is a well-known history of both collaboration and resistance, but go west and you see a bunch of complacent nations that were largely happy to be pinned under the Nazi boot, with the sacrifice of their Jewish populations considered a small price to pay for their relative peace after they were conquered. The Western nations also resisted refugees, taking only a small number of rich Jewish emigrees and even, famously, turning away shiploads of children. In contrast Jews fleeing east were welcomed into the Soviet Union, and it was the Red Army that liberated Auschwitz, discovered Treblinka, and rescued the Jews of Poland from Nazi violence. The West stood by and waited, taking far more interest in the recovery of their colonial possessions in Africa than in helping the desperate Jews of western Europe, and it was only when the Soviet Union began to roll over Europe itself that they suddenly conceived an urgent need to fight back against the Nazis. If Hitler had cut a deal with Poland to march his armies through for a direct attack on the Soviet Union in 1939, would the west even have bothered going to war with him? I suspect that they would not, and would have stood by while the fate of the Soviet Union’s Jewish population was determined.

This is a stain on Europe’s post-war liberal conscience, so how did they endeavour to wash out this stain? They handed one of their stolen colonial lands to the Zionist project, which immediately unleashed the Nakba on the people of Palestine and established an apartheid state on the shores of the mediterranean. Every time the people of Palestine attempted to peacefully resolve this conflict the Israeli state responded with violence and destruction, and so we find ourselves at the present state, where 2 million Palestinians languish in an open-air prison camp constructed with western money. When Hamas finally respond with a successful attack on Israel’s military, that blood-drenched state unleashes a wave of violence – first indiscriminately killing their own hostages, making up a 21st century blood-libel about beheaded babies, and then attempting to starve and bomb the population of Gaza into oblivion.

In response to this savagery the same liberal democracies and media outlets that were just two weeks ago giving a standing ovation to a confirmed Nazi, or defending that same action, or steadfastly looking away, suddenly rushed to condemn every unsubstantiated lie put out by the Israeli Defence Forces, and publicly announced their unconditional support for “the World’s Most Moral Army” as it enacts the first mass murder of the 21st century. They have nothing to say except “more!” as the IDF slaughters thousands of children, cuts off electricity from hospitals, and forces civilians to drinking from puddles. None of this is kept secret either – in contrast to the “genocide” of Uyghurs that the western media and intelligence agencies invented from whole cloth, and have presented to us constantly over the last 3 years without a shred of evidence, within minutes of the unfolding bombardment of Gaza our social media feeds are flooded with videos of dying children, bombed ambulances, buildings collapsed on civilians, reports of entire families wiped out. The Palestinian ambassador to the UK reports 6 of his own family killed; the Scottish first minister’s own mother-in-law is trapped in Gaza and he cannot even get a response to inquiries from the foreign office, while the media drill him on whether he has sufficiently condemned Hamas. Meanwhile France bans rallies in support of the Palestinian people, MSNBC bars its muslim anchors from reporting, a Muslim child is stabbed to death in the USA, and Germany stops a protest by Jewish opponents of the slaughter on the grounds it might be anti-Semitic.

This is the “liberal” response to the mass murder by starvation and bombing of 2 million muslims. Meanwhile liberal blogs – those bastions of interventionism back in the Iraq war days – remain stunningly silent. Balloon Juice, which has run a daily post on the invasion of Ukraine, headed with a graphic accusing “Ruzzians” of genocide, declared “there’s no there there” about the shameful Canadian ovation of a Nazi, and is in full support of the Israeli military. Lawyers, Guns and Money have barely mentioned it, and Crooked Timber have put up a single, weak post about how they don’t know what to say, which has degenerated into a condemnathon and some complaints about Jeremy Corbyn – the only politician of any note in the UK who was willing to publicly support the Palestinian people.

It’s often said that the single defining feature of liberalism is that liberals never, ever learn. They constantly watch the same things happening, hear the same lies from the same criminal gang, absorb the same excuses from the same people, and respond in the same way without any adaptation to the circumstances. We know that the Israeli Defence Forces lie – they lied about Shireen Abu Akleh, they lied about the Gaza Flotilla Raid, they lied about Rachel Corrie – but of course every person in the western media, political and public elite accepts everything they say without question, knowing it’s all a lie and knowing their history of killing children. Journalists, of course, don’t even have object permanence, but this singular property of liberal politicians and political commentators generally is that they cannot, under any circumstances, learn from what constantly surprises them, because if they developed any theory of the structural underpinnings of the social forces at work it would become simply impossible to remain a part of the liberal establishment.

Our failing economy

The last part of this collapse in the coherence of the western social order is our failing economy. We are constantly told – by political leadership, by economists, by journalists and by pundits and “think” tankers – that capitalism is the best system available to us, that capitalism has made us the richest people in the history of the world, that any other system would leave us impoverished and embittered. Yet at the same time they tell us that they have to cancel even the shortest high speed rail line because they can’t afford it; that university fees must remain too expensive for most people to attend without going into a lifetime of debt; that it is simply impossible for people to have affordable housing; and that paying you more than $7.25 an hour is beyond their power. You must remain poor, squatting in sub-standard housing surrounded by decaying infrastructure and scrabbling to get together enough money just to stay housed and pay off the exorbitant price of your university loans – all in the richest countries in the history of the world. Whose wealth? Whose benefit? They couldn’t even control a simple respiratory disease, you had to go back to work as soon as possible or the best, most efficient system of allocation of resources in the history of the universe would collapse around you; and they absolutely cannot afford to pay for you to get a booster vaccine if you’re under 50, because … well, because how could the 6th richest country in the world afford it?

And where did this money go? The USA spends a huge percentage of its income on weapons, is a thoroughly militarized society; the UK and France are nuclear powers. But together the entire economy of the NATO countries – some 500 million people, including most of the top 10 richest countries in the world – ran out of ammunition and weapons to give to Ukraine after just 600 days of war with a country having not even a third of their population. Where did all that money they took from you go? What were they spending it on, while they were telling you they can’t afford high speed rail, schools that don’t collapse, COVID protections, universal health coverage, gun control or a raise in the minimum wage? After 600 days they’re scraping the bottom of the barrel, right down to munitions they promised they wouldn’t use because they’re borderline illegal (and won’t work in Ukraine anyway). And worse still the wonder-weapons they sent have all failed, proven to be worse than the cheapest material the Russians can throw at them. All the Leopard tanks are burnt out husks, the Challengers – “never defeated in battle” – abandoned on the side of the road next to ditches filled with the corpses of Ukrainian men, the Bradleys and Bushmasters and Marders all toast and the troops they were slated to carry forced to slog through the long grass where mines and drones are slaughtering them. That’s what your money was spent on, while you were being told 10% annual inflation was inevitable and no you can’t have a pay rise, and if you try striking we’ll make it illegal because the best system of allocating resources ever invented – the only one that works – can’t make food affordable and can’t produce enough ammunition to fight a small war in a distant country.

So, this is the promise of liberalism as we enter the third decade of the 21st century. No freedom of speech, no money for you and no investment in public services, and if you dare to speak up while we throw money into the mass murder of civilians living in the poorest place on earth we will throw you in jail. In America we’ll throw you in jail anyway, but not until we’ve stripped you of your assets without trial and only if you’re lucky enough not to get shot on arrest. In defense of this you need to stand by and watch – you must not speak, or you’ll lose your job! – as we commit warcrimes and cheer the bombing of hospitals and the starving of citizens and throw all our resources into defending a criminal, corrupt gang of Nazis as they grind an entire generation of men into meat, only to find those resources aren’t enough because our economies are running on empty.

But if you talk about any of this you’re a wild-eyed idealist, a “tankie” (who paradoxically doesn’t want to send German tanks into Eastern Europe!), an anti-semite, and – worst of all – naive, unable to understand that this is the only way things can be. Nothing can ever ever be better, and anyone who tries to make it better is a fool and a trouble-maker.

This is liberalism in the 21st century.