I have been playing Star Wars recently with my regular group, first using the Genesys rules and (since yesterday) using a port of the Coriolis rules, because we’re all sick of Genesys. The Star Wars universe is fun and, like D&D or Lord of the Rings, has that particular positive quality that you can settle into it without knowing anything about it – it just feels familiar. Plus, running around on missions for the Hutts is fun, what could go wrong? However, it is beginning to feel like the Star Wars universe suffers the same problem I have identified with the Harry Potter universe – it is fine so long as it is kept within a very specific and narrow narrative framework but once you try exploring it freely as an adult outside its original confines it falls apart fast. I want to try examining how in particular the Star Wars universe is weird, first from the perspective of the weird inconsistencies in the amount of energy available to its denizens, then through a discussion of how we should interpret the inequality of the rim relative to the core in light of these calculations and what we know of its history, and then through some specific examples of how this affects e.g. energy weapons and the existence and behavior of Hutt space.

How Many Dyson Spheres do You Need?

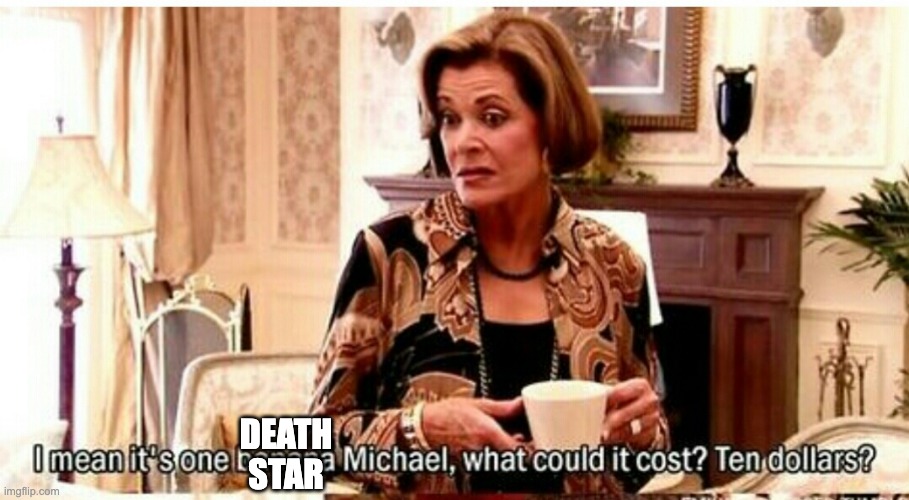

First let’s do some energy and energy density calculations, and introduce some reference values, by way of setting the context[1]. First, from this Forbes article (?) we can establish that the amount of energy required to destroy a planet like Alderaan is about 2e32 Joules[2]. That is, 2×10^32 Joules. Some quick online searches tell me that the sun outputs 4×10^26 Joules. So the Death Star is, to all intents and purposes, a Dyson Sphere wrapped around an artificially-created star, and because we know from the three original movies what the time frames are, it takes the Empire about 3 years to build one.

From a random and quite wild blog post we can estimate the death star to have a mass of about 2e18 kg, meaning that it has an energy density of an astounding 10^14 Joules per kg, if the whole thing was a giant battery. We will return to this information a little later. Here are some other random bits of information about energy:

- The population of the earth consumes about 2×10^20 Joules of energy per year, meaning that if we assume most of that energy is consumed by 100 million rich people, the average energy consumption of the richest societies on earth is about 10^12 Joules in one year

- If we assume an X-wing fighter weighs about 20tons, the energy required to accelerate this thing to 10000 x the speed of light (10k C) in one second would be about 10^4x3x10^8x2x10^4 (using energy required as mass times the final speed obtained, i.e. the change in momentum) which is, essentially 6×10^16, let’s say 10^17 Joules

- Apparently a star destroyer weighs 40 million tons, which means it would take 10^20 Joules to get to the same speed[3]

- A typical nuclear reactor produces a GW of power, which is 10^9 Joules

- The original steam engine, the Watt engine, invented 250 years ago, generates 6 horsepower or about 4200 Joules, 4×10^3 Joules. So over 250 years we have improved our energy generation capacity by a factor of a million. But note that nobody in the modern world uses a Watt Engine to do anything!

- A modern LIthium-ion battery has an energy density of about 750000 Joules, that is 7.5×10^5 Joules.

- A lead-acid car battery has an energy density of about 150000 Joules, which is 1.5×10^5 Joules. I think this means that energy technology has developed much more slowly than energy generation – let’s say at the ln() of the rate of energy generation[4]

- The Star Wars galaxy has a population of one hundred quadrillion sentient beings (10^17 people) over 1 billion (10^9) planets. I call bullshit on the latter number, since I’ve seen the map, but let’s go with it

- A typical nuclear reactor has a 30-70% energy efficiency, with the rest of the power escaping as waste heat. If this profile applied to the Death Star it would be as hot as the sun, so we have to assume that it has almost perfect efficiency in power generation

So let’s look at how some of those numbers work out. Dividing the energy in the Death Star by the population of the galaxy, we find that every time the Death Star is fired it generates enough energy to enable everyone in the galaxy to have a standard of living 1000 times better than the richest people on earth. During the battle of Yavin the Death Star was fired multiple times. Just to be clear I’m going to put this in quotes:

Every time the Death Star is fired it uses enough energy to maintain the entire sentient population of the galaxy at the standard of living of the richest people on earth for a millenium

So over the 3 years of the original 3 movies the Empire generated and wasted enough energy to maintain the entire population of the galaxy for about five aeons. By way of contrast, the Republic presided over an era of peace for a thousand years.

That’s a lot of energy! Another way to think of this is to imagine that the Death Star has an energy system that is 99.9999999% efficient, that is only 0.0000001% of the energy generated is lost during the firing process. This is obviously necessary, to ensure that the waste heat generated is orders of magnitude less than the temperature of the sun. That number is 10^-8%, or as a decimal, 10^-10. If an enterprising engineer on the Death Star noted this waste, they might be able to tap it, and would thus be able to drain off 10^22 Joules of energy – enough energy to maintain their home planet’s population for 100 years if their planet was as populous as earth. This is very similar to the situation in Harry Potter, where the magical world’s rubbish is valuable enough to muggles that they can use that rubbish to change their entire lives.

Another way to think about the energy differentials involved here is to contemplate the scale of energy required from an X-wing to a star destroyer to the Death Star: we go from 10^16 J for the X-Wing through 10^20 J for the Star Destroyer to 10^32 J for the Death Star, a factor of 10^16. Compare with the ratio of energy generation from the nuclear reactor to the Watt Engine, of 10^6. We are seeing people living in and working with devices with energy density that is so far below that of the peak technology that it is as if people living on earth were using windmills to power every aspect of their lives, as if every day we saw Watt Engines alongside nuclear reactors – but three orders of magnitude greater in difference. More like if there were people living in urban Tokyo who could barely produce fire, while the rest of us cruise by in nuclear-powered cars.

Post-poverty Science Fiction

The implication of this is first and foremost that the Star Wars galaxy has levels of inequality that are staggering by even the worst standards of earth. Every three years the society of Star Wars is able to build a Dyson Sphere wrapped around an artificial sun, and fly it almost instantly to anywhere in the galaxy, where they can casually blow off enough energy to maintain the entire population of the galaxy at elite standards of living for a millenium, but Luke’s Uncle Owen is struggling to get by on Tatooine as a moisture farmer, pawning broken-down droids off of passing Jawa who live in conditions little better than those of a 19th-century gypsy. Tatooine isn’t the only planet where we see this poverty: the forest-moon of Endor, the planet where we first meet Rei, Jah-Jah Binks’s planet, and pretty much every planet we see in Star Wars is living in conditions little better than or a lot worse than a typical rural area in 1970s earth. In a sense this is similar to how there are people in rural Nigeria who have modern smartphones and a TV but no access to modern health care and unreliable electricity. But the difference is that those of us in the Imperial core on earth do not have access to energy sources 10^16 times better than those people living in Nigeria. In fact the World Population Review suggests a maximum of eight-fold difference in energy use between poorest and richest regions (though it has limited data on Africa). The inequality in the Star Wars universe is staggering, so great that is essentially unmeasurable with any meaningful metric.

And it’s not like this is the fault of the Empire, either. We don’t see any evidence anywhere in the first movie that Tatooine is a once-great, super-rich society reduced to poverty by Imperial neglect or mistreatment – in fact in that movie the Empire has only been around a couple of years (a decade?) and the Republic “presided over a thousand years of peace.” All that inequality and ruin on the edge of the empire is the fault of the Republic, and nothing is presented anywhere to suggest otherwise. Now it could be argued that the Empire has been wastefully using resources on building mobile Dyson Spheres for war, which fair enough, but why wasn’t the Republic investing in these backwaters?

They deserved to be overthrown, didn’t they?

How small can a blaster be?

This also has consequences for in-game mechanics, which could be interesting or alarming depending on how you approach the fantastic scale of energy generation in the galaxy. While converting our system to Coriolis rules we have been discussing the damage blasters do, and trying to distinguish between blaster pistols and blaster rifles – Coriolis and Genesys both have low damage settings, which makes it difficult to easily distinguish weapons from one another since a sword might do 2 damage and a dagger 1. But I noticed, based on the scale of these energy values, that the ridiculous energy densities of the machines in the universe suggest that any blaster of any size would contain so much energy that it could effectively disintegrate a human being with a single shot, and the form and function of any blaster pistol or rifle in the universe is essentially aesthetic. Consider the X-wing, which weighs 20,000 kg and can generate 10^16J of energy. That’s 10^12J per kg, and much higher if you look at just the engines. Or a light saber, which can run forever on a battery the size of the palm of your hand with enough energy to cut through steel or humans. There’s no reason to suppose that a blaster pistol and a blaster rifle would have any noticeable difference in damage from each other. The battery required to provide essentially infinite shots of plasma capable of eviscerating a human would probably weigh a gram in the Star Wars galaxy. It’s entirely possible that a blaster rifle that actually had the Cumbersome-3 quality would have enough energy to collapse skyscrapers. I suggested we price blaster pistols and blaster rifles only by damage done, and that the difference between them was that the greater stability of a rifle configuration allows it to fire at longer range and to use the aim action. If we don’t do that then we are essentially working in a setting where our weapons are the equivalent of police in our own world carrying nothing more effective than pebbles, to fight gangsters driving tanks. If you look even superficially at the energies involved in the Star Wars universe you start to notice a lot of things are wrong!

How much effort is too little?

This stupendous inequality also has implications for the entire concept of Hutt space. In the original movies we don’t see any background information about the Hutts, except to know that Jabba is a notorious gangster lording it over at least one section of a backwater desert planet. But in the games (and I assume the broader canon) Hutt space is a sprawling zone of the galaxy that covers a pretty big wedge of the galaxy and spills over onto at least one major trade route (the Corellan route). This is an area that is supposedly only nominally under Imperial control, a situation that existed before the Empire, and is controlled by competing clans of Hutts who are essentially gangsters, who the Empire attempts to cooperate with but has been “unable” or “unwilling” to completely dominate.

But why? Why would an empire that can build two Dyson spheres in three years give a flying fuck what the Hutts think? Why would an empire that can mobilize soldiers from a population of a hundred quadrillion people, deliver them anywhere in the blink of an eye with spaceships that can generate more energy than most planetary economies, let this happen? One of my fellow players suggested that this is because controlling the Hutts is “too much effort”. But what is “too much effort” to a society that can fire off a millenium of luxury energy in a second, an economy so powerful that the waste energy from one of its flagships could fuel the industrial revolutions of a thousand planets? What, they get tired? It would take them a week to invest every planetary HQ of every Hutt clan, and when the leaders had all fled to Nal Shaddaa it would be the work of a couple of minutes to rock up and vapourize all of them. Or, if your Death Star is out of commission, you blockade that planet and wait 3 years to build another one, then rock up and vapourize them.

The mere thought or conception of rebellion is not even possible in a galaxy where your leaders can rock up with a Death Star on a moment’s notice. It’s not like ancient Rome where you get warning that the bastards are coming months ahead, as they cross rivers and ride over mountains. They just turn up, a couple of minutes or hours or days after they left their last system, riding on a Dyson Sphere wrapped around a star that they built, and you have precisely five seconds to pledge your allegiance, hand over the traitors or get turned to cosmic dust. And all you have in reply is the galactic equivalent of a pen knife.

Another argument for the Hutts is that the resources they ship to the empire in exchange for their nominal independence are a reward in and of themselves, but this makes no sense in a galaxy where you can build a Dyson Sphere wrapped around an artificial star, that is a weapon. Who is going to deny you anything? And what could you possibly need? The answer of course is Kyber crystals (which are apparently needed for your artificial stars) but what is an easier way to get them? Collaborating with a large criminal network, or rolling out so much energy and luxury goods that the entire galaxy is 100 million times better off than it was just 3 years ago, and everyone is happy to go along with your plans? If they stopped building star destroyers and Death Stars for just one year they would have so much energy that everyone in the galaxy could live in luxury like the Hutts. Who would be a gangster then? It’s inconceivable that the Hutts have anything the Empire would want that they cannot buy or take.

SF’s imaginary failures

It’s very easy when you are developing visions for new worlds to have them be incoherent and inconsistent on closer inspection. Almost all of them are. But it’s very interesting to me when they are incoherent in a way that suggests either that the fundamental social structure of the world is evil, as in Harry Potter, or the game designers really didn’t know much about how the real world works, as in Feng Shui. In this case the broader Star Wars universe seems to reflect both of these properties – I feel like people who understood how the real world works might have noticed the massive inequalities in their imagined world, and I also think they should have noticed that almost all of the social problems we see in the Star Wars galaxy are the Republic’s fault. Apparently George Lucas envisioned the rebellion as the Vietnamese and the Empire as the USA, but I think that’s a flawed vision since the rebellion is happening within the Empire, while the Vietnam war happened outside it (say what you want about the USA’s many bad geo-political practices, but Vietnam was not part of US territory before they started the war). And the inequality between the USA and Vietnam in the 1960s was not in the same order as the inequality between, say, Tatooine (not part of the rebellion!) and Coruscant in the Star Wars galaxy. In fact I would guess that the inequality between the life of a Roman Patrician and the poorest heathen resident of Britannia just by Hadrian’s Wall would have been smaller than the gap between Admiral Ozzel and Luke Skywalker. George Lucas didn’t have to think about this much, just as he didn’t have to waste much time on the structure of Hutt space, because we just got glimpses of all this stuff, fragmentary visions of a world of good and evil laid out before us as we romped through it. Was Jabba the Hutt even a planetary-level gang boss? Who knows! But once you develop the extended universe you have to figure this out, you have to systematize these ideas. I personally think it would have been much better to have the Hutts not be gangsters overall, not have a concept of Hutt space, and have Jabba the Hutt be a unique gangster in command of a single planet’s underworld, as others of other races are in other isolated parts of the edge of the empire. But no amount of careful world-building can overcome the enormous, staggering inequality at the heart of the galaxy, because it’s there in the original canon.

Better examples of how to handle these problems are shown by Iain M. Banks’s Culture series, or in Firefly. In the Culture series we see a society that might be capable of building a Dyson Sphere (they probably would consider it too trashy a thing to bother with), but they don’t hoard the tech – they distribute all energy and wealth freely to whoever wants it, and nobody lacks for anything except by choice. This is the only logical endpoint for a society that has so much spare energy floating around that it can build its own stars and wrap a Dyson Sphere around them every 3 years[5]. There’s no rebellion from within the Culture because nobody needs anything from anyone, there is no inequality or even money. It’s luxury space communism!

In contrast, Firefly also takes place on the edge of the empire, in outlying colonies living in grinding poverty, lawless planets and systems where gangsters control the lives of poor and desperate people while the elites in the centre look the other way or send punitive expeditions to meddle in the lives of these people on the edge who they see as trouble-makers and scoundrels. But the society of Firefly doesn’t have infinite resources, can’t build Dyson Spheres, doesn’t have the power to blow up planets, in fact can’t even properly run a randomized clinical trial of a happiness drug. There is still inequality but it is believable in its magnitude, exists for explicitly social reasons and is the central friction driving the plot. In contrast, in Star Wars we never really find out why there is a rebellion. They don’t like the Empire, something about freedom etc, but we don’t see anything about the material or political structures underlying this rebellion. All we know is that the location of the secret rebel base is in the hands of a Princess. It kind of stands to reason that there would be staggering inequality in a Republic run by Princesses, doesn’t it? But we don’t get to ask any of those questions.

To be clear, it’s fine to me that this happens in the original three movies, I’m down with the Rebellion as soon as the show starts and I don’t need any motivation to be on Luke’s side, I know how to watch a movie. Blowing up Alderaan confirms for me that the Empire are the bad guys, even though I don’t know what the Republic did to people. That’s okay in the movies, but now my character Dita Voss is doing these jobs for the Hutts and I’m having to figure out why in this galaxy we even have Hutts and gangsters and human trafficking and poverty and contract workers in the shadow of a Dyson Sphere. Once I start exploring the broader galaxy of the expanded universe, and thinking about things like how smuggling works, why the Hutts run this system, why these planets are so poor, who I should really be trying to kill, I begin to run into big inconsistencies in the way it’s all laid out. And given the recency of the Empire, and the obvious persistence of these problems, I am starting to think I need to look further back in time to find someone to blame. And Dita Voss is starting to wonder if there is a Quelchrist Falconer she can turn to, who might have a better plan for the future, in which the Death Stars get turned on all the ruling houses, then melted down into ploughshares.

We will need something, after all, to plough all that blood and bone into the soil of our new utopia, once those distant star lords have been dragged out of their towers of infinite energy and down into the dust beside us.

fn1: A word of warning, it has been 30 years since I studied thermodynamics and electromagnetism so I may confuse some measures of total energy and flow of energy. Be patient with me!

fn2: I think that article suggests we can lower the amount if we assume it uses the planets gravitational dynamics against it, but this is inconsistent with the use of the Death Star’s main weapon in Return of the Jedi to blow up spaceships, which have no meaningful gravitational effects.

fn3: Here I’m assuming no special amount of energy required to break the light barrier or do the weird physics of hyperspeed, and assuming that the punch to light speed takes about a second. I chose 10,000 so that an X-wing can travel about 10 light years in half a day, which is consistent with the amount of time it took the pilots in Episode IV to get to the Death Star from their rebel base. An alternative method is to imagine that the hyperdrive converts their mass to energy and then transfers it, in which case the formula would be mass x 10^16 (E=mc^2, a formula originally identified by Chewbacca); in that case an X-wing requires 10^20 J and a star destroyer 10^24. But note if this is the case that the Death Star would require ~10^34 Joules to enter hyperspeed, which is more than is required to blow up Alderaan and is the energy of 100 million suns. I can’t abide those numbers! But feel free to update the wildness of this post with higher figures for hyperspeed if you want.

fn4: You could argue that this is unreasonable since batteries didn’t exist when the Watt Engine was invented, and that in a galaxy a long way away and a long time ago they just have different battery tech. The light saber certainly seems to suggest so

fn5: And remember, once you’ve built one of these bastards the next one is easier. You now have the energy of a million suns at your disposal in one mobile platform that moves faster than the speed of light, you can do anything, build anything. Need resources? Rock up to an inhabitable planet and turn it to rocks, then send in the mining drones …