My theory is no; but I’m sure Herge would beg to differ, as would the artist who conceived of the idea.

Compromise and Conceit

Infernal adventuring…

-

Primo Levi’s The Truce is a beautiful book that contains many insights into the human condition. For those who have not had the good fortune to read this masterpiece, it describes the year or so period over which Primo Levi recovered from his experience of Auschwitz and his return to Italy. Having been rescued by the Russians, Levi necessarily spent his time recovering in refugee camps and transit centres in the Soviet Union. In additional to his remarkable insights into the nature of humanity, Levi also gives us a unique picture of Russia under Stalin. Unlike most western writers of the time, he was not writing about his time in Russia in order to criticize or applaud communism; his experience was entirely tangential to it, and although thankful to his Soviet liberators and potentially a sympathizer (since a leftist during the war), he had no particular broader political motives for his book. This is about as unbiassed a snapshot of Soviet life as you could hope to get at the time, and it is remarkable for one common theme : chaos. Contrary to our image of communist life as regimented, strictly controlled and highly authoritarian, his experience of the Soviet Union was one of chaos, easy movement, rules flouted, and a kind of free-floating easiness of life that one wouldn’t expect in this putatively rigid society. One could argue that this was a consequence of the immediate confusion of the post-war era, but I don’t think this can be all of the reason: we know that the Soviet Union launched vicious crackdowns in its territories when the war was over, and very efficiently looted East Germany; surely if they had wanted to they could have run their refugee camps, railway stations and behind-the-lines towns with an iron fist. But they didn’t, and this surprised me when I read the book. One doesn’t associate chaotic and disordered, highly transient and quite libertine lifestyles with an immediate post-war Stalinist state.

Recently I have been reading a book called Passage to Manhood: Youth Migration, Heroin and AIDS in Southwest China, by Shao-hua Liu, which is a book about the development of heroin addiction and the HIV/AIDS epidemic in minority Nuoso people in Sichuan province, China. The book is based on ethnographic research carried out by Liu during 2005-2009, and describes the particular social and cultural context in which heroin addiction spread through this community. It’s billed as a work of “medical ethnography” and it certainly doesn’t disappoint in this regard. It’s a very interesting read! Although the fieldwork was conducted in the 2000s, much of the discussion concerns past events in the lives of the research subjects, and many of these past events focus around criminality: historically the Nuoso have entered manhood by looting neighbouring Han Chinese areas and taking slaves, and as modernity overtook their communities this practice shifted from looting neighbouring areas to going on journeys to large cities and engaging in petty crime in places like Chengdu, Xi’An, or even Beijing. The book contains accounts of some of these activities.

This is interesting because it gives us an insight into the interaction of criminals from an ethnic minority (supposedly discriminated against in China) with China’s public security officials. China is supposedly highly authoritarian and has a strong police force, large prison population, etc. So one would expect that there would be a fairly robust response to Nuoso criminality, and some evidence of the pervasive nature of Chinese authoritarianism. In fact, we read more of the same kinds of thing as Levi described. For example, in one passage we discover that an area of Han Chinese in Chengdu got permission from the police to set up an extra-judicial police force to patrol their areas and prevent Nuoso from entering them unless they had identification. You would think that a strong central state would prohibit private groups from this sort of thing, unless (perhaps) they were officially-supported militia. But compared to the states dealings with the Han Chinese, when they interact with Nuoso criminals things really get chaotic. Let us consider three examples.

The Mummy Clause

In one instance, a mother was arrested for drug dealing in Yunnan province and sent to a detention centre. The mother had a baby of several months who she was nursing, and so her family petitioned the local Communist Party to let her go for a year so she could nurse her baby. They did, on the condition that she return to detention after a year. At the end of that year she absconded and returned to drug dealing in Chengdu. The story does not contain any suggestion that the police were able to follow her. This is an example of an informal judicial arrangement being made for an ethnic minority mother – is it consistent with our expectation of a strong Chinese security apparatus?

Public Cremation

In Nuosu theology, it is very important to cremate the body of a dead person, and to return at least some of their skeleton and ashes to the family so that their three souls can gain proper rest. Of course, for homeless Nuosu drug users in big cities far from their homes, this is very difficult. Many Nuosu died of drug overdose and had to be cremated in the cities where they died, but this often cost far more than even a wealthy Nuosu could afford. In one account, a Nuosu man describes his experience of burning the dead in the parks of Xi’an:

One time, in the middle of a cremation on the fringes of Xi’an City, policemen suddenly arrived and accused me of being a murder. I told them, “I didn’t kill him. He was my own brother! We Yizu [minorities] do this to teh dead all the time.” I showed the policemen the dead man’s hukou[registration card]. I thought it might be needed, so I had brought it with me from Limu. I also gave the policemen the telephone number of the Zhoujue County Police Station. They made a call to the Zhaojue and realized that we Yizu do cremate the dead this way. So they didn’t arrest me but warned me not to burn bodies this way anymore.

So this is the fearful Chinese police in action. They catch you burning a body in one of China’s major cities, and they ask you not to do it again, and decide not to investigate a murder, after calling a rural police station and being told that this sort of thing happens. Can you imagine if you tried burning a body in a bit of scrubland on the edge of the city you currently live in, and the police caught you? Would it be sufficient to say “I can’t afford a crematorium”? If an Aboriginal man tried to do a customary burning of a body on the outskirts of an Australian city, would he be let off with a caution by passing cops? I think not!

Anti-drug Campaigns

The author also describes the initial efforts by Chinese police to break up drug dealing in the Nuosu towns. Having initially left it to the local Nuosu elders (“lineage groups”) to resolve the problem – itself not the sort of behaviour one associates with a state that is oppressing minorities – the police finally started acting on the increasing problems that were being experienced in these towns. In one instance they broke up a group of youths who were watching tv in front of a school. The Nuosu being interviewed tells us

Everybody ran and hastily threw the drugs behind the TV set. The police arrested a five-year-old boy who happened to pick up a small packet of drugs! His lineage headmen complained to the police about their arrest of an innocent kid and finally were able to take him back home.

What happened to the terrifying police? Where are their powers of arbitrary detention? What about using the kid as a hostage to enforce good behaviour by the barbarian minority?! What about swapping the kid for a drug dealer, or sending the lot of them to work camps? And just precisely how official and intimidating and well-organized could this raid possibly have been, when everyone was able to run and throw their drugs behind the TV. Imagine if the police in your country did a drug bust, and your level of terror of them was sufficiently low that throwing your drugs behind a communal tv would be sufficient to get you out of trouble.

I’ve seen COPS, and I don’t think that things would have panned out quite the same way for a group of young men from an American minority in the same situation.

This is not the kind of thing one expects of a society with a strong police state, where untold hordes of people are supposedly shuffling around in re-education camps, while those who are “free” yearn for the real freedoms of the west. In fact, the USA has a much higher rate of imprisonment than China, and debate about whether China has a more punitive public security system than the US centres around the numbers of unofficial prisoners (the shambling hordes in the work camps) and the treatment of minorities. This book suggests to me that the Chinese handling of (non-political) crimes is much less punitive than the US, and more chaotic and based on individual discretion (not always a good thing) and that there is a lot of confusion in its public security apparatus. It also suggests to me that their system of handling minorities is not as oppressive as some commentators would have us believe.

As ever, nothing of what we’re told by our friends in the media can be trusted…

-

Apparently the makers of Godzilla are going to make a new film, Palin vs. Bachman: Battle for the Teapot. That will definitely trump The West Wing!

-

A new style of television that is part horror, part sci-fi, part drama and part comedy, Psychoville represents a huge artistic step forward for the makers of the League of Gentlemen. Of course, when we use the word “artistic” in connection with something by this group we don’t mean “beautiful” or “aesthetically pleasing”; but a step forward it undeniably is. They have taken the basic comic horror format of that original (brilliant) show and developed it to a new level of drama. This new drama combines the creepiness and horror of the original League of Gentlemen with poignant human drama developed between carefully constructed characters, whose motivations unfold in great detail over the course of just six episodes. The characters are developed in great depth over a mere 6 episodes, some (like the fag-hag Hatty) drawing on classic stereotypes to build classic horror characters; while others, like Mr. Jolly (“keeps kids quiet!”) show a depth of creative talent that is hard to believe is possible in such a short format. Simultaneously repulsive, engaging and affecting, Mr. Jolly the failing clown is a leap forward in comic horror. For examples of his brilliance, see the Clown Court (poor quality) or the Clown Funeral. The Sourbutts (mother and son) show the true creativity of this team, though. They are very, very disturbing in their closeness and their hobbies, hilarious in their stupidities, very touching in their human warmth, and ultimately a great example of a sad and close familial relationship. I think this is a new form of television, in which the grotesque and classically horrific is combined with comedy and real human drama. The development of the Sourbutt relationship over two short seasons – a total of only 12 episodes – shows, I think, really tight and carefully developed writing, as well as extreme acting skill.

These achievements are made all the more memorable by the fact that most of the main characters are played by the same three (?) people. Occasionally the make-up breaks and you can see what they’re up to but mostly it’s brilliant. But in this show – unlike League of Gentlemen – they have not used excessive levels of macabre to hide the effects. The differences are carried by the acting, and the careful mixing of the separate stories across the series so the viewer never becomes accustomed to any single person in the play. The plot itself is also very clever, drawing together disparate stories and mixing in new ones where necessary to bring a group of seemingly completely unrelated people together into a very carefully integrated story. In both seasons the climax is very clever and complete, drawing together even the smallest parts of the previous episodes to make a complete whole. Anyone who GMs regularly knows how hard this is to do, and a lot of screenwriters have failed in this task at the last hurdle, but the creators have done a sterling job of drawing the threads of the story together to a satisfying end.

This style of television is definitely not to everyone’s tastes. It’s by turns disgusting, pathetic and disturbing; sometimes the make-up fails and the viewer is left depending on their own willingness to suspend disbelief. But if you can stomach the terrible characters and the occasional excesses, you will witness something new being created for television. The whole thing is on youtube, and I recommend watching it if you have the chance, if only so you can watch masters of plot and acting in the fullness of their craft – or alternatively, just for the clown court…

-

Weighing in at 55kg plus hair, in the Blue Corner… Apropos of nothing, here is the website of one of the brothels that operate in my local suburb, Kado Ebi. I walk past this brothel (actually, it’s a soapland) on my way to my favourite restaurant, Bloomoon, or when I’m passing Kichijoji’s hammock cafe[1]. It says a lot about the attitude towards sex in Japan that a brothel can be situated opposite a fashionable cafe for dainty young women. I suppose it also says a lot that the brothel has a website, multiple branches, a search facility to match you to your favourite “princess” (including by blood type), pictures of the inside of the brothel on the website, and an announcement saying that the brothel doesn’t employ kyakuhiki, that is, touts. This is what happens when you decriminalize sex work (I think in Japan all forms of non-penetrative sex are completely legal as sex work, though I could be wrong about this).

But what really confuses and intrigues me about this soapland (besides the name, which I think means “corner shrimp”) is that, in addition to providing the much-needed service of an all over body wash and wank for 6000 yen (about$US60), it also has a sign out the front advertising its boxing school. That’s right, this soapland is running a boxing school, which is somehow connected to the soapland and is advertised via a sign on the wall outside: “We’re looking for students!”

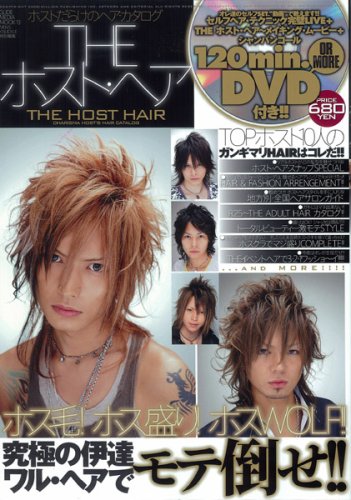

Who thought it would be a good idea to connect their boxing school to a brothel? Is it a school of fighting for the local pimps and touts? Is there some deal where the girls who work at kado ebi get to stay trim in the boxing gym, maybe beating up their clients? Maybe they thought it would be easier to provide ring girls if the boxing gym is inside a brothel… do they share bathrooms? This phenomenon is genuinely and completely a mystery to me. Guesses or suggestions as to what’s really going on here much appreciated. Also, my partner’s moving to Tokyo in a month, and she’s been doing a bit of boxing with a group of handsome Korean boys in Beppu. Should I recommend to her that she take up boxing at the Kado Ebi gym? She does like host hair, after all …

—

fn1: Passing this cafe is a classic moment of being able to appreciate the strangeness of Japanese women. There they all are, sitting daintily eating and drinking and chatting on their hammocks, everyone swaying slightly, heads bobbing about as the hammocks move slightly. It’s a picture of cuteness – the cafe is always completely girl-only, girl-focused, with these girls all talking very intently to each other in a very civilized way, swaying daintily on their hammocks. It’s like the hold of some fantasy anime pirate ship…

-

Guess who's cumming to dinner? Despite the many controversies that beset it, 300 is a very impressive queer cultural critique. I was sitting in a bar last night watching the ending, and mulling over how brave the director was to attempt a mainstream blockbuster movie focussed so strongly on the cultural politics of homosexual relationships. To the best of my knowledge it’s the only mainstream blockbuster movie ever made that lookd directly at the confused politics of sexual relations in the queer world. While on the surface, on a trivial reading, it’s a piece of visually stunning warporn, the director very cleverly used this warporn both to lure in mainstream heterosexual audiences, and to model the socio-sexual relations of the gay bathhouse. Basically here we have a movie that uses battle scenes to recreate the visceral chaos of a gay sauna, and to investigate the complex relations of dominance, submission and manipulation that exist between “tops” and “bottoms” in this world, or at least in this world as its cultural stereotype is understood by most queer critics.

The battle scene-as-sauna is a powerful and unique contribution to cinema. The gangs of faceless men in the background, struggling and sweating, the chaos and the intense physicality of battle, when eroticized in the unique style of the movie, are a brilliant analogy for the sexual milieu of the bathhouse. Others have struggled with ways of representing homosexual activity that don’t offend the mainstream, but the battle scene conveys all the essential elements of sex in a culturally acceptable way, without any transgressions. We have sex as death, an age old image that everyone understands; we have a “battle” conducted entirely with piercing weapons; and we have the slaying of another, so often characterized as the pinnacle of masculine responsibility, as a metaphor for sexual conquest, also so clearly construed as a masculine role. The moment of death as orgasm, the petit mort of everyone’s experience, the exhaustion of the fighters after a hard “battle,” and the image of war as expression of self… what is this but warporn as porn?

Nowhere is this war imagery more usefully exploited than in the climactic scene, where we see also the heart of the movie’s queer cultural critique. The key to the movie is to understand it as a metaphor for the deployment – and ultimately the frustration – of power by a “bottom,” represented in the form of the Persian emperor, to undermine the will and strength of a “top” (Leonidas) and of “tops” as independent men (the Spartans). For those unfamiliar with this politics, let us put it simply. In many popular imaginings of gay sex, both straight and queer, the world of gay men is divided into two types: “bottoms,” who are fucked; and “tops,” who fuck them. Fundamentally this is based on a misogynist construction of women as fucked and man as fucker; in the classic misogynist imagery, women have “power” that they can deploy in the form of seduction, to undermine the will of the man and to set him on a path – they are the power behind the throne, Lady Macbeth, using their feminine wiles in a way that the misogynist construes as infinitely more powerful than we mere men possess (control of the state, the family and the means of production) – all these things fall to the wayside at the sight of a perfect arse, in the misogynist construction of woman-as-betrayer. As old as Genesis[1], this misogynist trope also infects the imagery of the gay “top” and “bottom,” with the “bottom” seen as “having the real power” through their ability to seduce, deceive and manipulate.

In 300 the director deconstructs this vision of the “bottom” as deceiver, and a clear judgment is made on the true state of power relations between the fucked and the fucker. The Persian Emperor – the ultimate (or nadirical?) “bottom”, manipulates hordes of men in the bathhouse (battlefield). They fuck (kill) each other in vain attempts at conquest, all to try and protect their claim to him, or to stake a claim thereon. The Spartans here are construed as tops, while the faceless Persians are merely other bottoms, deployed by the ultimate bottom as objects to be fucked (killed) in his attempts to bring the “tops” to accept his power. Ultimately the Spartan’s efforts are futile – no matter how many they fuck (kill), they must ultimately exhaust their strength. But at this moment, instead of seeing them bow to the superior manipulative power of the “bottom,” we see his power rejected ultimately – it is shown to be false and shallow, based as it is on the weakness of others rather than the strength of self. The two “tops,” finally exhausted by their orgy (battle), look to each other in exhaustion, and declare their undying love for each other. Then one of them – Leonidas – draws himself to his feet for one last effort. Bringing forth his cock (spear), he hurls himself at the hated “bottom”, and shows his true feelings for the manipulator. The tip of his weapon rips off the Emperor’s decorative chain and slashes his cheek, splattering blood across his face. In 300 we understand, immediately, that blood symbolizes cum, and so we see at the end of the movie the cumshot in which all modern porn must end. The “tops” have shown their undying love for each other and at the last one of them expresses his contempt for the “bottom” in the traditional way – with a cumshot. And so the Emperor’s victory is shown to be hollow, to have been achieved only through the public display of his own sexual humiliation. At the last, the “top” chose independence and another independent man, and showed the bottom to be nothing but an object of scorn and sexual degradation.

Is this not a powerful critique of a style of sexual relations? And all conveyed within a visually powerful, strongly homoerotic movie that is at times stirring, exciting and poetic. Though many will disagree with the interpretation of sexual relations shown in the movie, I think we can all accept that as cultural critique, it is unparalleled in its intensity, ingenuity and power. A masterpiece of subtle social critique deployed through completely unsubtle images, and presented in such a way as to achieve mainstream success. I can only hope that it will inspire other queer cinema to emerge from its “indie” lacuna and into the limelight!

—

fn1: though probably not as old as Phil Collins

-

I have a colleague – let’s call her Miss P – who lived in Australia for a few years, in Melbourne and Perth, and has a bank account there (with ANZ). She had some questions today about her account, and has tried calling a few times but is daunted by the English required, so today I called on her behalf. What followed is a classic example of the excellence of Australian service.

Stage 1: The General Line

We called the general help line, and a middle-aged-sounding woman answered the phone.

- Me: explains situation, asks first question

- Her: Gives slightly confusing answer, then says “But actually, it’s probably just easier for Miss P if she calls the overseas line, because they’ll be able to find her an interpreter.” Gives me number.

- Me: Perfect! Thank you. We’ll try that.

This is cool! So off we go…

Stage 2: The Overseas Line

We call the overseas line. A youngish-sounding chap answers, and after my explanation he transfers me to some other department in customer service. Here I’m greeted by another middle-aged-sounding woman with a very strong Australian accent.

- Me: explains situation and asks for interpreter

- Her: Oh yes, we can definitely do that. What you need to do is call Miss P’s bank branch, and they’ll find her one [what is this, every ANZ branch has a UN office inside it?]

- Me: Okay, could you tell me the number

- Her: tells me the number, then says “How about I transfer you? Just a moment.”

Unfortunately, the phone cut off (we’re using Skype). So … we call directly.

Stage 3: The Local Branch

So we’re calling a bank branch in Perth. Let’s just get that clear right now. Another middle-aged-sounding woman answers the phone, and has a very broad accent and speaks slowly and clearly. Excellent. I don’t think she’s going to be our interpreter though…

- Me: explains situation and how we just got cut off. “I was told you could maybe arrange an interpreter?”

- Her: Ooooh, mmmm, I don’t think we do that here, but just a mo [<- she actually said this], I’ll see if anyone here can help

- Me: Okay, thank you …

- …. long period on hold …

- Her: Hello, um I’m sorry but I’ve called around a couple of departments and they don’t seem to have any service like that in this branch.

- Me: Oh, we were told you would have

- Her: Well, I don’t think we do. But I tell you what [<- she actually said this], the Surfer’s Paradise branch might have an interpreter. There’s a lot of Japanese up there! Hold on a mo [<- she actually said this] and I’ll give it a go [<- she actually said this].

- … short period on hold …

- Her: Hello! We’ve found someone in Surfers [<- she actually said this]. I’ll just put you through…

Now, just for clarity for my foreign reader(s), Perth is in, well, Perth is in Perth. Surfer’s Paradise is in Queensland. This is the opposite end of the country. This is literally, actually, like someone in London saying “just a moment, I’ve found a Russian speaker in our Moscow branch. I’ll just transfer you.” That’s the distance involved here.

Stage 4: “Surfers”

So we get transferred to “Surfers” and this time we don’t get cut off. A moment later a youngish-sounding woman answers the phone.

- Her: Hello, this is M [<-Japanese name] speaking, do you need a Japanese speaker?

- Me: Yes I do, my colleague Miss P needs to ask some questions and it would be much easier for her if she can do it in Japanese. Are you the interpreter.

- Her: Yes I am, please put her on the line

- Miss P: もしもし、Mと申します。よろしくお願いします

The conversation proceeds as I write this. Miss M had a Japanese accent mixed with ‘Strayan, a phenomenon that is extremely funny. She must have lived in “Surfers” for quite a while. And so, international communication was able to proceed smoothly …

How good is that service?

On a related note, my ‘Strayan is sometimes hard for my students to understand. The other day, while speaking to my Chinese student, who is doing a dynamic model of HIV epidemiology in China but is concerned she has overestimated the price of needle syringe programs, we had the following exchange:

- Me: Are you using the retail price of needles?

- Her: Um…

- Me: ???

- Her: What do you mean “retile”?

- Me: [putting on my international accent] Oh, “retale” means an object sold through a normal shop, not like through a big warehouse

- Her: Oh, you mean “retail!” Oh yes, I’m using the retail price, but even if I …

If I influence someone’s english long enough, they’ll even pick up the lilt… “I’m goin’ to the hospital to die…”

-

The Guardian today has an article on gold-farming in China about gold farming in Chinese labour camps, which claims that prisoners in labour camps in China were (are?) forced to play computer games at night after they had spent the day at hard physical labour. The prison then sold the products of their labour to free[1] computer gamers, but of course the camp workers saw none of the profits. If they failed to produce sufficient gold, or slacked off in their virtual world, they were beaten and punished in other ways. The article presents some interesting information about the way gold farming is conducted in labour camps and also in IT sweatshops. The latter represent “voluntary” labour and those doing it seem to think it pays better than factory work (it’s probably safer too), while the former are involuntary work.

These gold farmers in labour camps are being essentially forced to go and work in another world for 7 to 10 hours a day, and beaten if they don’t produce the goods they’re sent there to get. Not only is this process surreal (literally!) but it’s a model of human trafficking, enacted virtually. Are we witnessing the development of an industry based on trafficking in virtual people?

—

fn1: if you can define WoW players as “free” by the standard definition of the term…